Highly anticipated from director Jordan Peele, Nope delivers an original multi-genre mash-up that questions historical and contemporary trends in cinematic exploitation. It’s an enjoyable watch, but one that, by the end, doesn’t quite reach the heights of Peele’s 2017 debut, Get Out.

Nope is set in an arid gulch surrounded by California desert and rock. Here sits Haywood’s Hollywood Horses, a ranch we see pass to OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya) following the death of his father in a freak accident. His sister Emerald (Keke Palmer) helps out when she’s not busy making a name for herself in the entertainment industry. In his father’s absence, OJ does his best to keep the ranch, which provides horses to film productions, profitable. Amid the humdrum of day-to-day life, the siblings’ grief over their father’s death, and the stress of keeping the family business alive, something peculiar simmers just below the surface…or just beyond the clouds. OJ is clearly unwilling to accept that a coin that fell from the sky with enough speed to penetrate his father’s skull was nothing more than a “bad miracle,” and with all the on-edge and disappearing horses, technological failures, and unusual skyward sightings haunting the ranch, OJ isn’t wrong to think so.

*It is very difficult to discuss this film without spoiling things; if you have not yet seen the film, I recommend that you stop reading here.*

The siblings realize there’s a UFO skulking around the gulch, gobbling up horses and spitting out any inorganic matter—this shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise if you’ve seen the official trailers. Emerald concocts an idea to capture evidence of the extraterrestrial; she wants to score not just any shot but an “Oprah shot” that they can sell for a pretty penny. They collect a small team, including an employee from Fry’s Electronics, Angel Torres (Brandon Perea), who invites himself after curiosity gets the better of him while he’s helping the Haywoods set up security cameras at the ranch, and a well-regarded cinematographer, Antlers Holst, (Michael Wincott) whom Emerald recruits

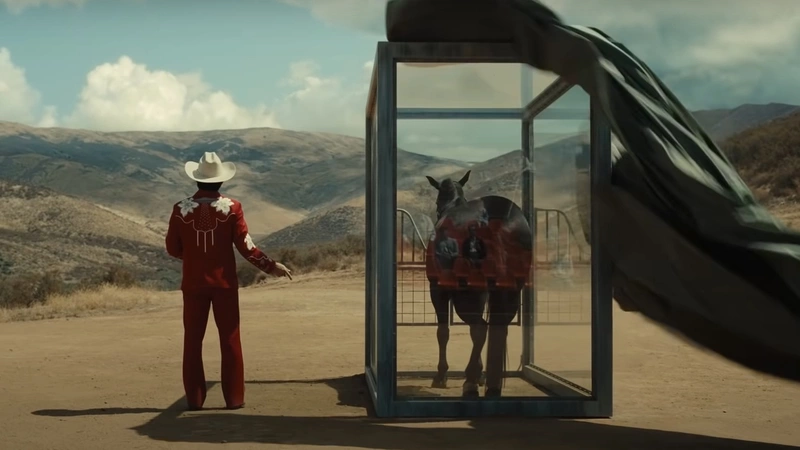

Nope, as has been noted by many critics, is a love letter to classic Hollywood—part of a current trend in contemporary cinema, horror included (think Ti West’s The House of the Devil and James Wan’s Malignant, both homages to horror’s past). The most recognizable reference, perhaps, is to Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film Jaws. The alien creeping through the clouds while the ragtag film crew cautiously scans the sky is immediately recognizable as an echo of the boat crew scanning the water for signs of a fin. And the demise of the alien by explosion following its consumption of a giant balloon is highly reminiscent of the way the shark meets its end. The homage to Westerns is delightful; OJ is a classic quiet and reserved cowboy, and the final shot of him on one of his remaining horses is at once nostalgic and powerfully subversive. So is the way Peele has chosen to frame his sci-fi Western; these are usually set off of Earth, with space standing in for the Wild West—the new frontier. Nope brings science fiction to a Western rather than a Western to science fiction. The score matches the film’s fusion of genre with a heavy influence from classic Western scores.

Despite so much of the film being rooted and inspired by the oldies, it has a satisfying freshness to it. The greatest twist in the film is the revelation that the strange disc sweeping across the Agua Dulce sky isn’t an alien vessel but the alien itself. In its first form, it resembles a manta ray, a smooth disc with a round orifice through which it sucks up its meals; when the chase begins, it takes on a jellyfish-like form. Both evoke Jaws through aquatic shapes—this is a sea creature of the sky. It’s not just the creature’s originality that elevates the film; the characters also breathe life into it. The sibling relationship between OJ and Emerald feels believable—complex but tender. They, and everyone else in their alien-hunting group, are quirky and real and bring the humor Peele’s career used to be centered on. It’s a welcome contrast to the eerie, desolate backdrop.

This is the third entry in Peele’s feature-film directorial catalog, building on the success of Get Out and his second picture, Us. We’re used to Peele’s films saying something, so much so that Twitter believes his films are birthing the newest generation of “film bros” eager to mansplain film symbolism to anyone in close proximity. Some viewers have claimed that Nope is a departure from Peele’s previous projects, citing an absence of social commentary in this latest film. But the change here is not toward less commentary; it’s in the way Peele is presenting it. The messaging in Get Out was in no way heavy-handed, but it was overt; it delivered, and forced the audience to face, a clear message. In Us, the message is much more hidden, but the film is so dense with metaphor it’s almost hard to enjoy. Nope is different. It doesn’t argue for or force upon us a message; it considers and it contemplates, but a message is certainly present and meaty enough to fuel plenty of discussion on the ride home from the theater.

While Nope is a film that celebrates classic Hollywood, it also asks us to consider the darker side of the industry and to examine the exploitation and worship of spectacle that cinematic media has invited and continues to invite into our society. The film opens with an apt Bible verse, Nahum 3:6: “And I will cast abominable filth upon thee, and make thee vile, and will set thee as a spectacle.” This is immediately followed by a scene that, at first, doesn’t seem like it’s going to fit with the rest of the movie—I actually thought it was some sort of short. A chimp stands alone on a film set, looking around nervously as alarms blare. From there, Peele cuts to a film set where the Haywood’s are working on a set for a commercial. The horse OJ has trained gets spooked and kicks in the direction of one of the actors, leading to the director abruptly deciding to use CGI rather than live animals—a huge setback for the Haywoods, who, to make ends meet, have already started to sell some of their horses to a nearby Wild West theme park owned by former child star Jupe (Steven Yuen).

The use of animals in horror films is always interesting, if often just a forewarning and foreshadowing of what’s to come. Peele has used animals symbolically in every one of his films: deer in Get Out, rabbits in Us, and now a chimp and horses in Nope. Add in the fact that the alien creature behaves like a wild animal itself—driven by hunger and fear, as opposed to a desire for world domination—and we’re left with a zoo of animals, a fitting metaphor to make a point about spectacles.

Jupe’s subplot drives home the connection between the animals in the film and its ideas about exploitation. It’s revealed that Jupe is a former child star whose nineties sitcom came to an end when a chimp actor went berserk and started attacking the cast and crew—the cold open scene being the moments immediately after this. Jupe’s explanation for this is that the chimp had simply reached its breaking point, an animal forced into a role it didn’t choose or ask for. Though the scenes with the extraterrestrial are suspenseful, the flashback to the chimp’s rampage is easily the most chilling in the film. Despite (or maybe because of) Jupe witnessing something so traumatic as a child, he has an unusual relationship with the incident; he has a private exhibit of memorabilia from the show, which he charges people to visit. It’s an exploitation of the consequences of exploitation.

Jupe meets his end for a similar reason. As it turns out, he too knows about the alien in the area, and he, like Emerald, has a business idea. The newest show at his theme park is designed to draw the extraterrestrial into view using those horses purchased from the Haywoods as bait. At the show, the life form eats up the paltry crowd of spectators—including Jupe’s former co-star, whose face was scarred and disfigured by the chimp. Guess she didn’t learn her lesson the first time.

We have to wonder why Jupe didn’t learn his lesson either. His business ventures emphasize just how obsessed we are with exploitation in the name of money and fame, but there’s more than that. Nope isn’t a film about race—not in the way Get Out is. But it’s hard to discuss exploitation without bringing it up. Jupe’s relationship with his traumatic childhood is informed, in part, by the fact that the chimp did not attack him. Finding him hiding under a table, in fact, the animal gave him a fist bump, as if to say, “I get it, dude.” There is some degree of kinship and shared experience between the animal and the Asian-American child actor, both exploited by people who demand entertainment from them. Jupe seems to have misunderstood what this kinship means, taking it to mean that he is now able to exploit others because of his own experience of being exploited.

Jupe, of course, is not the only one to try to exploit the flying extraterrestrial. Peele shows us exploitation from different angles. We get a sense of his line of thinking. What if Jaws (or something like Jaws) happened today? How would people react? In today’s culture of spectacle and exploitation, characters emerge: the curious one, the ones trying to make a quick buck, the ones trying to create or maintain a legacy, the artists, the sleazy tabloid writers, and the showmen. Each of them has their own motivations in looking to exploit the creature; many are destroyed in the process.

Jordan Peele noted in an interview with GQ that his own goal was to make “the big summer blockbuster spectacle film.” While he comes close, I don’t think he quite gets there. I’m not sure if in 50 years it will be seen as a classic the way Jaws is and the way Get Out likely will. In a way, though, the shortcomings of the film only accentuate its message. The end feels anticlimactic. The beast is slain…and then what? Perhaps I’m part of the problem—I need to see the drama, I need the spectacle, I need to see what becomes of the siblings. But if your goal is to make the big summer blockbuster, then that follow-through is necessary.

Nope is clever and, as with all of Peele’s films, it’s tons of fun to pick apart all of its conscious choices; this review could easily have been twice as long. It’ll leave you wanting to rewatch the classics it references while also ruminating on the way we engage with media and spectacle. You may find yourself giving a more scrutinous look at the motives behind our focus on punches thrown at the Oscars and televised court cases like the OJ Simpson trial (yes, OJ Haywood’s name is likely in reference). The film narrowly misses being fantastic, as the ending falls a bit short, but if you’re a genre fan, forgoing a viewing would be a mistake.

Good movie. Good review