The height of the COVID-19 pandemic required creativity of filmmakers barred from traditional moviemaking with large crews and casts. One response was the revival of a fan-favorite genre: found footage. Deadstream is the latest in a short string of found-footage films featuring contemporary technology and our relationship with social media. With its clever take on influencer culture and online livestreaming, Deadstream manages to thrill, disgust, and amuse the audience in ways that similar films have been unable to achieve.

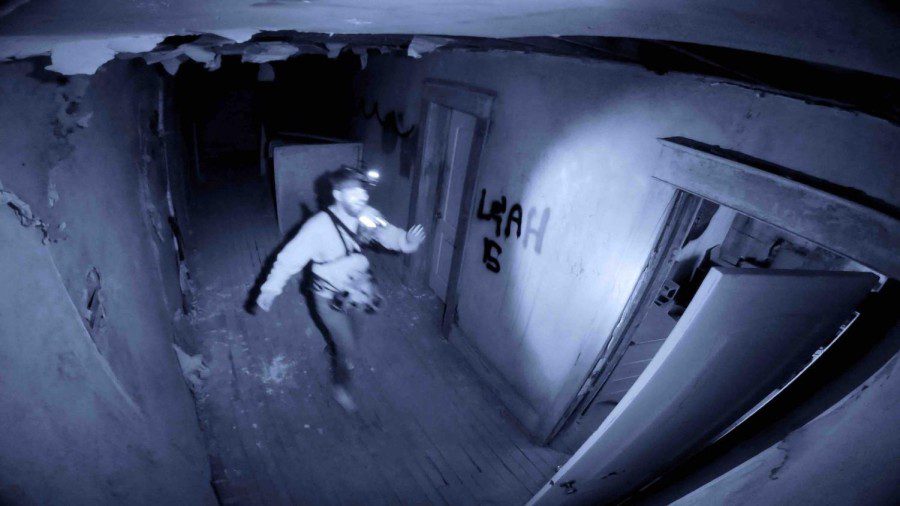

Deadstream depicts a livestream, on a fictional Twitch-like service, of an online personality named Shawn (played by Joseph Winter, one of the writer–director team). His shtick is filming himself “facing his fears” by doing various risky/ humiliating stunts, until one stunt badly damages his reputation to the point of demonetization of his content. He’s now trying to restart his streaming career by spending a night trapped in a purportedly haunted house. After locking himself inside “Death Manor” and throwing away the key, he explores the house room by room, setting up cameras and interacting with his audience through his streaming service’s chat feature. We learn that the house is supposedly still inhabited by the ghosts of Mildred Pratt—a failed poet who died by suicide—and other former inhabitants. In one of the bedroom closets, Shawn finds an occult-looking symbol drawn on yellowed paper, which he promptly destroys, leading to a hellish night alone—well, alone with his millions of viewers.

Deadstream plays as if it’s the livestream itself. It isn’t the first to use this framing. One of the earliest was Cam (2018) which follows a cam girl having her identity and image stolen; an unknown person or entity locks her out of her account, leaving an eerie doppelganger in her (virtual) place. (2014’s Unfriended came first, strictly speaking, but doesn’t have much else going for it.) This movie has become ever creepier in retrospect, as deepfakes and AI technology grow more sophisticated year by year. However, while some of Cam is presented directly as a livestream, most of it occurs off the computer, and is filmed conventionally.

Director Rob Savage, by contrast, has created two films in recent years that are framed entirely as found footage or fictional broadcasts. The first, Host (2020), which was released during the strictest period of COVID-19 restrictions, follows a group of friends who host a Zoom seance to chase away lockdown boredom only to meet a disastrous end; the film utilizes the different camera feeds on Zoom to showcase constrained views into the homes of the participants and the horrors they face. Even close to Deadstream is Savage’s Dashcam (2021), which like Deadstream features a grating livestream host. Annie Hardy (a thinly fictionalized version of the actor who plays her) gets fed up with lockdown in L.A. and streams her travels to London to visit a former bandmate through her iPhone and dashcam—and inadvertently captures footage of a demonic entity brought forth by a satanic cult and trapped inside a 16-year-old. The two streaming-related films achieve showcasing streaming interfaces and the hosts’ interactions with their followers look and feel believable. (Something of a feat compared to films from a decade ago with their awkward, trying-too-hard text speak and very obviously fake app interfaces.)

Both Dashcam and Deadstream exemplify the new direction found-footage horror is going in; the bottom-line difference between them is that Deadstream is done better. One particularly clever choice by the Deadstream team, allowing them to present more traditional film footage within the film’s livestream frame, was to have Shawn set up cameras in each room of the house so that his viewers could keep an eye out for ghosts away from Shawn’s first-person perspective. Usually, found-footage horror limits the viewer’s perspective to that of the person holding the camera; this is certainly one of the most effective ways Dashcam increases tension. In Deadstream, however, multiple perspectives do the same, as Shawn’s viewers witness things creeping through other frames before he does and the chat box fills up with messages of support for, hatred of, or indifference toward Shawn.

Much of Deadstream’s superiority to Dashcam comes down to the difference between the streaming personalities at the center of the two films. To be sure, both are obnoxious. But Annie Hardy tips into galling; she’s an anti-vax, anti-mask, COVID-denying Trumper, and her yammering about these beliefs and copious cursing (and car rapping), though funny at first, become tiresome. A quick perusal of the real-life Annie Hardy’s Twitter reveals that her character is barely fictionalized; she really is a right-wing, anti-vax, “anti-woke” online personality who streams herself rapping from her car. There doesn’t seem to be much of a purpose to the film beyond Savage wanting to capture “the mad chaos of Annie Hardy.” Clarisse Loughrey makes an interesting observation in her review, noting that “when the whole world’s coming at you through a screen, it becomes increasingly hard to tell the difference between life and entertainment”; the fictional Annie Hardy is a conspiracist who is disbelieved by her audience after showing them authentic evidence of the possession she’s witnessed. However, I’m not sure we can credit the commentary on truth and credibility to a conscious choice by Savage rather than a coincidental outcome of stunt casting, which waters down and muddles what could have been an interesting take on online conspiracy culture and the reliability of the media.

Shawn in Deadstream, on the other hand, isn’t closely based on any one streamer or YouTuber. He’s an amalgamation of various personalities, a generic but familiar character. This better serves as a base for satirical, though not deep, commentary on internet culture. One plot detail in particular hammers on the absurd vanity of being an online personality: Shawn’s need to get back into the good graces of the internet and rebuild his following mirror Mildred’s desire for an audience for her poetry. At the beginning of the film, we know that Shawn is doing this stunt as a Hail Mary to win back his viewers and sponsors, but we’re not yet privy to what he did wrong. His desperation is obvious in every moment when he wants to chicken out but is reminded by viewers that he has to continue or lose his sponsors; his petty false bravado anytime he’s called out is a great recurring joke. Through videos linked in the comments by viewers (a semi-corny aspect of the film), Shawn discovers that Mildred has made a deal with a demon to bind the spirits of former residents to her in order to have a permanent audience for her poetry. He makes the iconic observation that the two of them are the same in their wishes for a following—a ridiculous but hilarious connection between online culture and the “content creators” of yore.

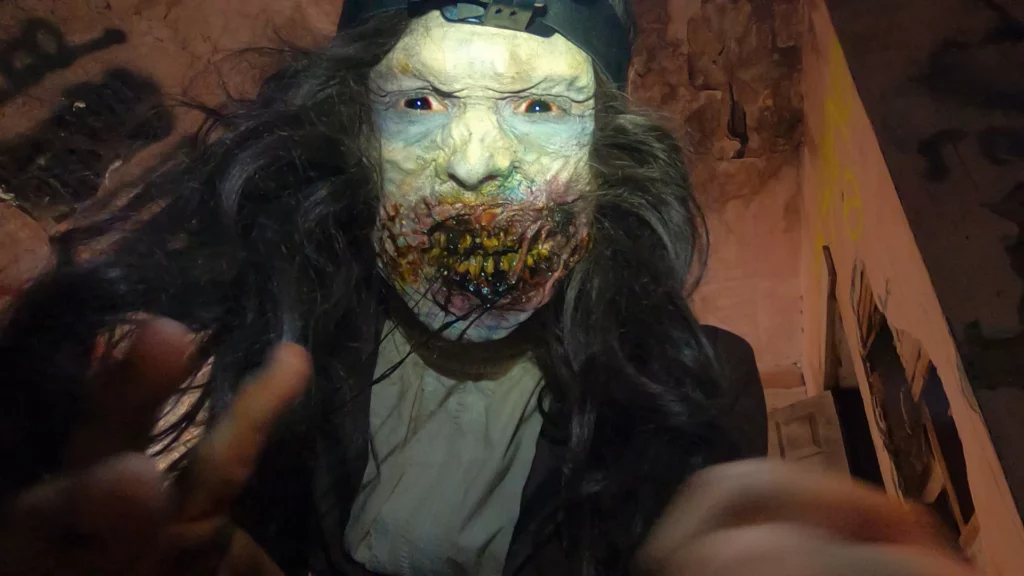

Deadstream’s special effects are campy and gross. Dashcam’s are good but never quite reach the enjoyable ridiculousness of Deadstream, which are reminiscent of Evil Dead II in their disgusting but comical nature—like the running joke of Mildred sticking her dead pointer fingers up Shawn’s nose as she squeals with laughter, even leaving a nail behind in one instance. Despite its comedic undertones, Deadstream still manages to genuinely startle with some well-executed jumpscares and tussles with ghosts. A lot of the humor is thanks to Joseph Winter’s performance; with many, many cameras trained on him and few co-stars, he needs to have a certain chemistry with himself, which he pulls off. In an interview with Macabre Daily, filmmakers Joseph and Vanessa Winters note that they fine-tuned the comedy in the film through audience testing, something that Dashcam could have used more of.

A small note on many other reviews I’ve read while writing this one: I don’t think we can call found footage a “gimmick” any longer. It is very clearly its own subgenre that is loved by many and has continued to evolve over the last 25 years; movies like Deadstream and the V/H/S revivals are proof of this. The Winters are clearly big fans of the subgenre; they also directed a horror short in V/H/S99—one of the only reasons to watch that one. It’s evident throughout their feature-length film, too, with multiple references to other films and common tropes, including holding up a joke sign at the beginning of his stream stating that Shawn hasn’t been seen since the livestream and an explicit reference to The Blair Witch Project. Even the scenes in which Shawn is having his nose picked by Mildred’s bony fingers have a zoomed in, overlit quality reminiscent of the unforgettable scene in The Blair Witch Project highlighted on that movie’s cover.

Deadstream does have one notable flaw, though, and that’s its inability to build and maintain any substantial tension. Perhaps it does have to do with the many cameras, which interfere with a major source of suspense in found-footage film: the limited view. It could also have to do with the heavily comedic tone. There are frights and a few brief rises in suspense, but much of the film involves Shawn getting scared and running from room to room without a genuine sense of dread or fear for his safety.

Cinema has to continuously adapt to changing trends, technology, and circumstances. Deadstream is a prime example of a film that does this well, taking a trope once dismissed as gimmicky and producing something that celebrates what came before it and what may come after it with humor, effective frights, and relevant social commentary. Joseph and Vanessa Winters have charmed me and are a duo I will be excited to follow in the years to come.